Complete History of the Basilica of Saint-Denis

Explore the story of the first great Gothic church — from early sanctuaries to royal necropolis and modern restoration.

Indholdsfortegnelse

Abbot Suger’s Vision & Dedication

In the 12th century, Abbot Suger reimagined the ancient sanctuary at Saint-Denis, seeking a space that would invite worshippers to encounter the divine through beauty and light. He called this ‘lux nova’, a new light, achieved through architectural invention and the theological imagination of his age. With daring clarity, he opened walls to stained glass and drew structure into rhythmic order, so that columns, ribs, and arches carried not only stone but meaning.

Suger’s project gathered artisans, donors, and ideas from across Christendom. It was both practical and poetic: a rebuilding that served a royal abbey, welcomed pilgrims, and articulated a mature vision of how materials, color, and proportion could draw the mind upward. What began in Saint-Denis continued across Europe, making the basilica a cradle of the Gothic spirit and a touchstone for generations.

Construction and Engineering

The basilica’s fabric is a lesson in innovation. Rib vaults channel weight with remarkable efficiency; pointed arches adjust gracefully to differing spans; slender columns rise with an almost musical cadence. The 12th-century choir introduced radiating chapels around an ambulatory, giving space for liturgy and devotion while opening the building to light in carefully choreographed ways.

Later work extended and refined the structure — nave, transept, and towers evolved through medieval ambition and modern necessity. Storms, time, and revolution tested the building. Engineers and masons responded with reinforcement, consolidation, and judicious reconstructions, keeping the basilica’s character intact while honoring the lessons of its pioneering design.

Design & Architecture

Saint-Denis translates theology into geometry. The play of verticals and curves, the proportional relationships between bay, column, and vault, and the orchestration of stained glass produce a unified experience: a luminous order where color and stone converse. The rose windows gather the day into a circle and release it across the nave; chapels unfold like side notes in a grand composition.

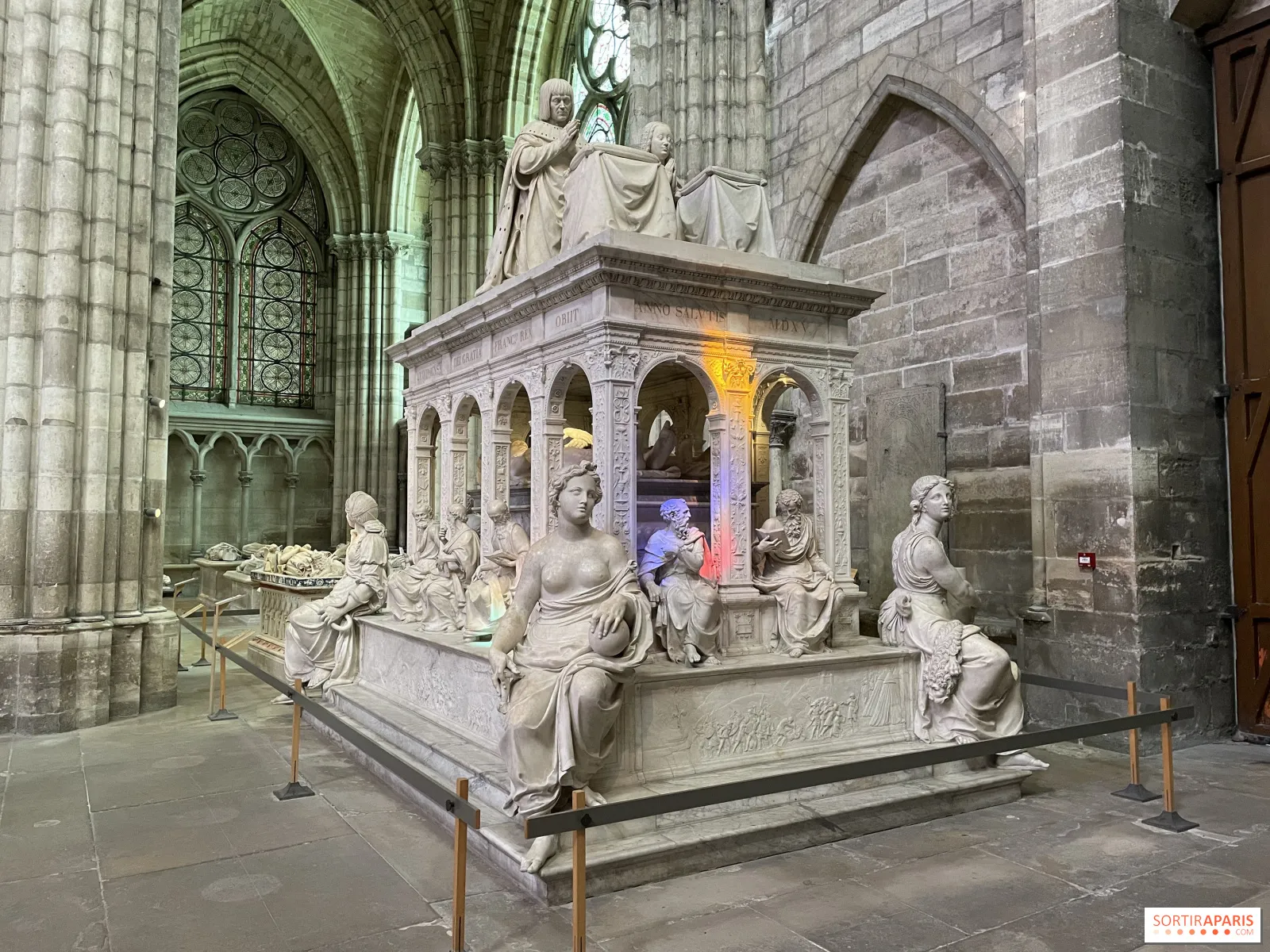

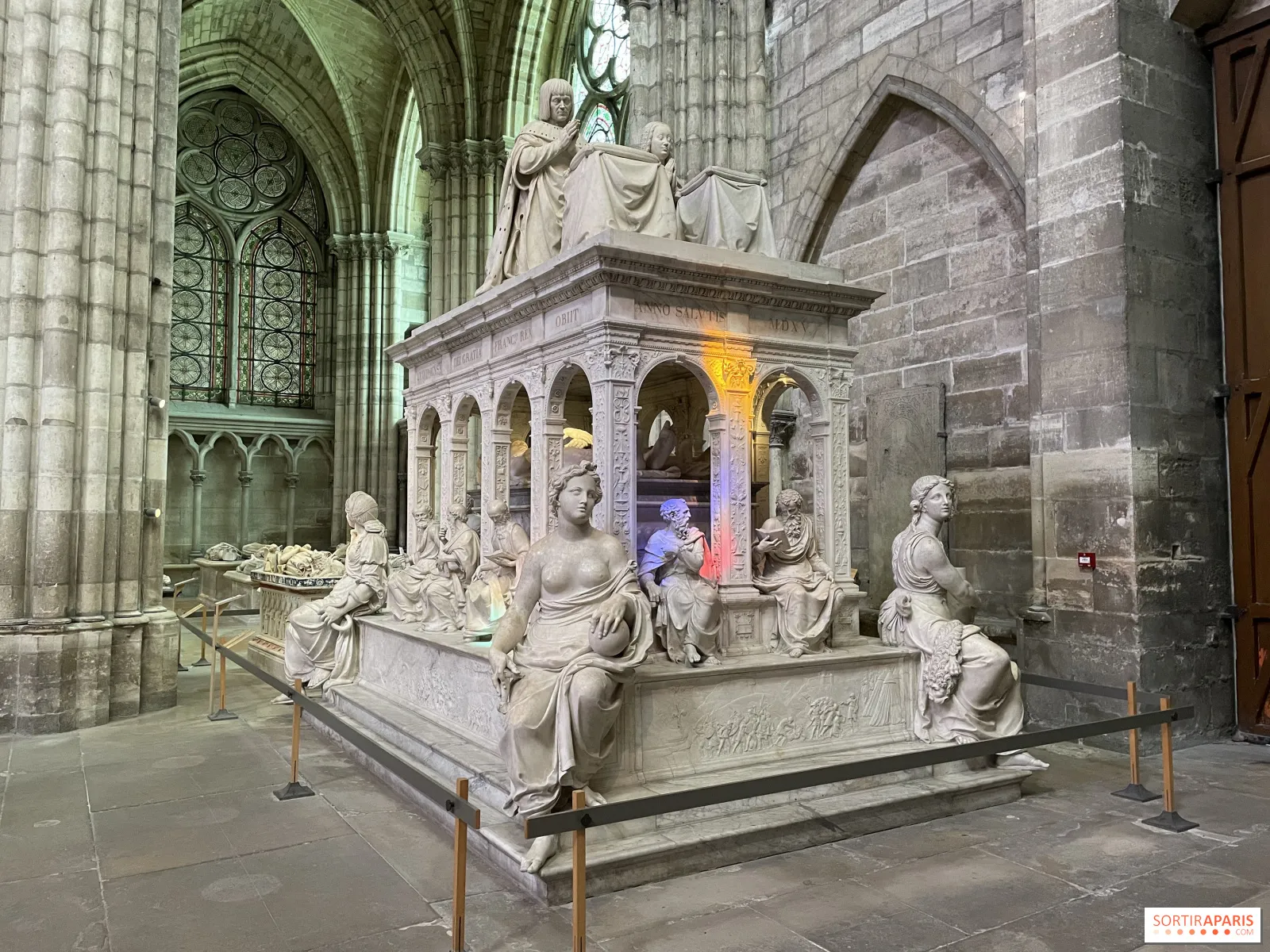

Decoration is purposeful. Capitals carry stories, portals frame thresholds with sculpture, and funerary art shapes historical memory in marble and alabaster. The building’s Gothic grammar — ribs, points, tracery, light — became a language that moved through Île-de-France and beyond, copied, adapted, and enriched wherever churches sought to stage the sacred with architectural grace.

Art, Symbolism & Ceremonies

Art at Saint-Denis is not ornament alone; it is a network of meanings. Stained glass narrates scripture and virtue; sculpture celebrates kingship and mortality. The royal necropolis holds effigies whose faces — serene, noble, sometimes intimate — make the past present, inviting us to reflect on continuity and change.

Ceremony has long shaped this space: royal processions, funerals, and liturgy once intertwined the basilica with national life. Today, services continue, reminders that Saint-Denis is both museum and living church. The coexistence adds depth: spiritual rhythm complements historical inquiry, and the building breathes in two tempos at once.

Preservation and Restoration

The French Revolution brought damage and upheaval — tombs were desecrated and remains disturbed, a stark chapter that reshaped the necropolis. The 19th century answered with documentation, careful recovery, and restoration campaigns led by architects including François Debret and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who sought to stabilize and clarify the basilica’s form.

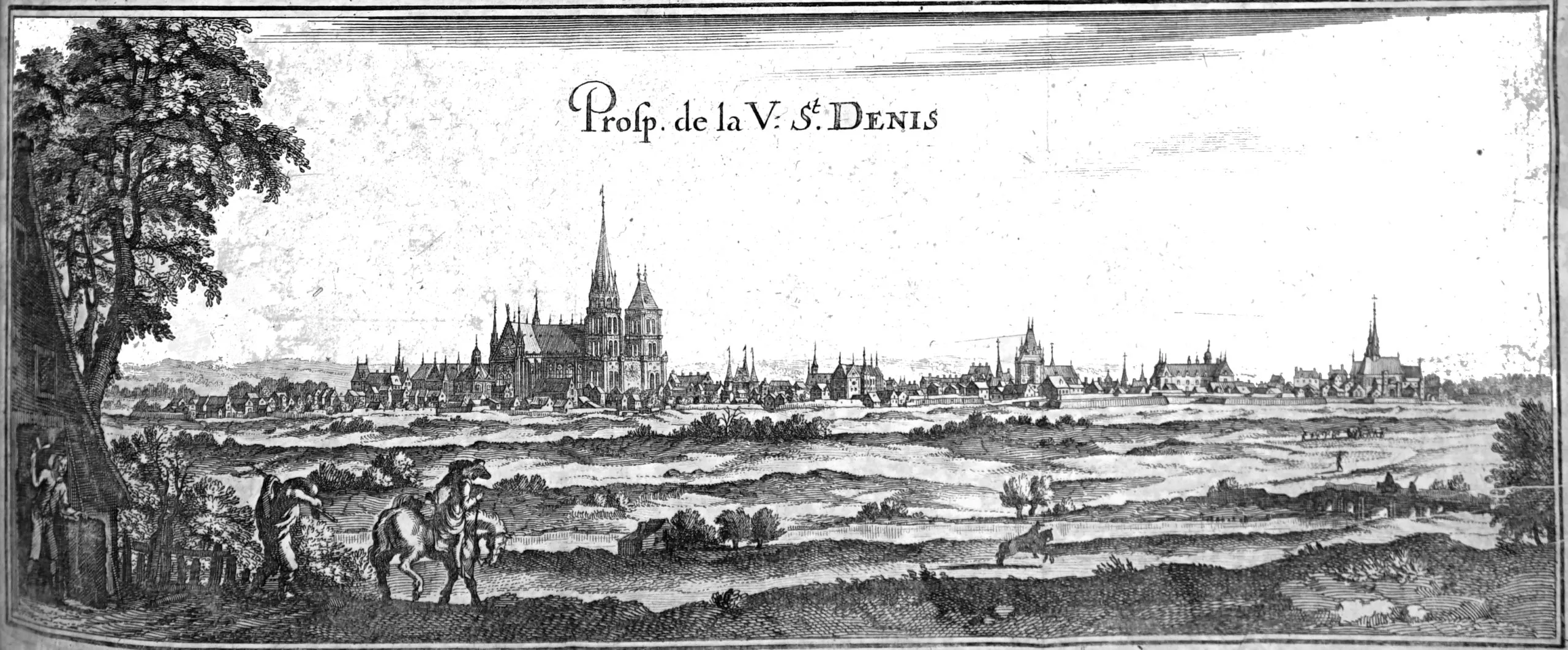

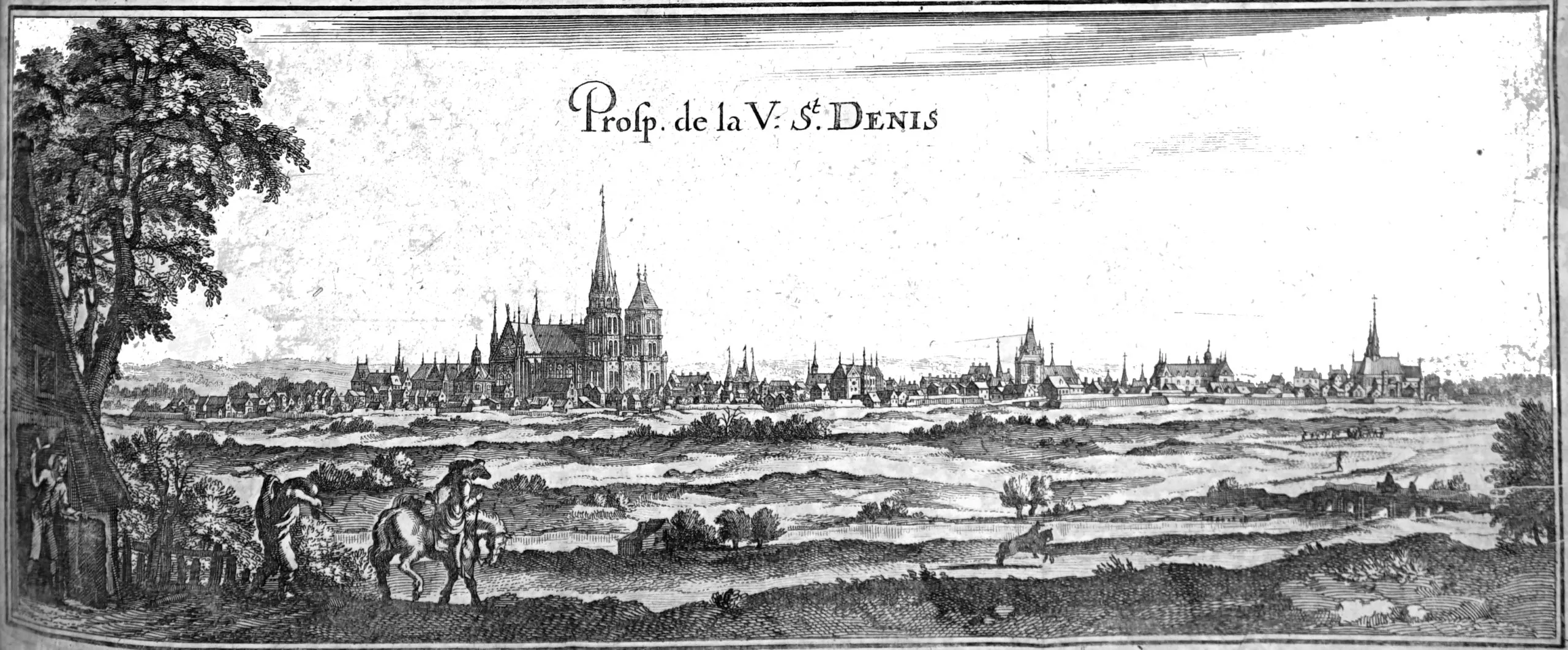

Modern conservation continues the work: cleaning stone, consolidating joints, safeguarding sculpture and glass, and studying the building’s behavior under contemporary conditions. The removed north spire remains a subject of debate and hope; plans to reconstruct it speak to a wider desire to share the basilica’s skyline as once imagined — always with respect for evidence, safety, and context.

Cultural Impact & Media

Saint-Denis appears in scholarship, films, and travel writing as a place where architecture changed direction. It anchors stories about monarchy, revolution, and the persistence of beauty under strain. Students come to learn Gothic’s vocabulary; visitors come to feel how space can shape thought and mood.

From textbooks to documentaries, the basilica serves as a reference point — not only for its historical firsts, but for the way it integrates art, light, and ritual into a coherent whole. Even casual images of its choir communicate a balance of strength and delicacy that has inspired artists and architects for centuries.

Visitor Experience Over Time

Pilgrims, monarchs, scholars, and tourists have crossed this threshold for almost a millennium. The experience has evolved with interpretation, signage, and conservation, yet the essential gestures remain familiar: look up, slow down, let the light lead. The necropolis invites a quieter gaze, the crypt a reflective pause.

As restoration deepened, safety and accessibility improved. Audio guides and tours now help decode the building’s language, making its innovations legible to modern minds. Saint-Denis has become a classroom of stone and color, welcoming generations to learn and to feel.

Saint-Denis during the Revolution & WW2

The Revolution’s desecration in the 1790s marked a traumatic moment: tombs opened, remains displaced, symbols contested. The basilica endured as a wounded witness, later receiving careful efforts to sort, honor, and present the necropolis with dignity and critical clarity.

During World War II, the basilica faced the hardships of occupation and scarcity but survived with limited damage. Postwar decades renewed study and conservation, reasserting the building’s role as a place of culture, worship, and shared heritage.

Saint-Denis in Popular Culture

Though quieter than Paris’s celebrity landmarks, Saint-Denis appears in cultural narratives about the origins of Gothic, the French monarchy, and the northern suburbs’ layered identity. It is sometimes a setting in historical novels and documentaries, a stage for thinking about beginnings and memory.

Its images — rose windows, effigies, choir — travel widely in books and media. For many, the basilica’s fame is intimate: a recommendation from a teacher, a morning of unexpected wonder, a realization that light can feel like thought made visible.

Visiting Today

Today’s visit balances discovery and care. Clear routes guide you through nave, choir, tombs, and crypt; interpretation highlights key moments and meanings. The basilica’s neighborhood adds texture — markets, cafés, and the everyday bustle around a monument that remains a local anchor.

Accessibility has improved where feasible; advance booking reduces waiting; and a range of visit formats let you choose between quiet contemplation and in-depth guided exploration. The basilica rewards time and attention — a place that feels larger the longer you look.

Future Preservation Plans

Conservation plans look to the basilica’s long horizon: stabilizing fabric, studying glass and stone interactions, and, for some, reviving the north spire as a patient, evidence-led project. Debates are thoughtful — weighing history, feasibility, and the values at stake when shaping the skyline anew.

Ongoing research, training, and community partnerships support a living heritage model. The goal is not perfection but stewardship: a resilient basilica that welcomes worshippers and visitors, and a clear record of how we care for what we inherit.

Nearby Paris Landmarks

Explore Saint-Denis’s lively market and square, stroll the Canal Saint-Denis, or pair your visit with the Stade de France. Montmartre and Sacré‑Cœur are a metro ride away, offering a contrast of hilltop views and 19th-century piety.

Head back toward central Paris for the Louvre and Île de la Cité, or discover La Plaine’s contemporary venues. Saint-Denis is a hinge — a chance to connect medieval innovation with modern urban life.

Cultural & National Significance

Saint-Denis is the cradle of Gothic and the resting place of French monarchy — a double heritage that binds architecture and national memory. Its stones articulate a vision where beauty serves understanding and ritual meets the responsibilities of power.

As a living church and monument, the basilica remains a place of encounter: between past and present, local and national, art and devotion. It teaches patience and attention — how to read light, how to listen to stone — and honors the continuity of care across time.

Indholdsfortegnelse

Abbot Suger’s Vision & Dedication

In the 12th century, Abbot Suger reimagined the ancient sanctuary at Saint-Denis, seeking a space that would invite worshippers to encounter the divine through beauty and light. He called this ‘lux nova’, a new light, achieved through architectural invention and the theological imagination of his age. With daring clarity, he opened walls to stained glass and drew structure into rhythmic order, so that columns, ribs, and arches carried not only stone but meaning.

Suger’s project gathered artisans, donors, and ideas from across Christendom. It was both practical and poetic: a rebuilding that served a royal abbey, welcomed pilgrims, and articulated a mature vision of how materials, color, and proportion could draw the mind upward. What began in Saint-Denis continued across Europe, making the basilica a cradle of the Gothic spirit and a touchstone for generations.

Construction and Engineering

The basilica’s fabric is a lesson in innovation. Rib vaults channel weight with remarkable efficiency; pointed arches adjust gracefully to differing spans; slender columns rise with an almost musical cadence. The 12th-century choir introduced radiating chapels around an ambulatory, giving space for liturgy and devotion while opening the building to light in carefully choreographed ways.

Later work extended and refined the structure — nave, transept, and towers evolved through medieval ambition and modern necessity. Storms, time, and revolution tested the building. Engineers and masons responded with reinforcement, consolidation, and judicious reconstructions, keeping the basilica’s character intact while honoring the lessons of its pioneering design.

Design & Architecture

Saint-Denis translates theology into geometry. The play of verticals and curves, the proportional relationships between bay, column, and vault, and the orchestration of stained glass produce a unified experience: a luminous order where color and stone converse. The rose windows gather the day into a circle and release it across the nave; chapels unfold like side notes in a grand composition.

Decoration is purposeful. Capitals carry stories, portals frame thresholds with sculpture, and funerary art shapes historical memory in marble and alabaster. The building’s Gothic grammar — ribs, points, tracery, light — became a language that moved through Île-de-France and beyond, copied, adapted, and enriched wherever churches sought to stage the sacred with architectural grace.

Art, Symbolism & Ceremonies

Art at Saint-Denis is not ornament alone; it is a network of meanings. Stained glass narrates scripture and virtue; sculpture celebrates kingship and mortality. The royal necropolis holds effigies whose faces — serene, noble, sometimes intimate — make the past present, inviting us to reflect on continuity and change.

Ceremony has long shaped this space: royal processions, funerals, and liturgy once intertwined the basilica with national life. Today, services continue, reminders that Saint-Denis is both museum and living church. The coexistence adds depth: spiritual rhythm complements historical inquiry, and the building breathes in two tempos at once.

Preservation and Restoration

The French Revolution brought damage and upheaval — tombs were desecrated and remains disturbed, a stark chapter that reshaped the necropolis. The 19th century answered with documentation, careful recovery, and restoration campaigns led by architects including François Debret and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who sought to stabilize and clarify the basilica’s form.

Modern conservation continues the work: cleaning stone, consolidating joints, safeguarding sculpture and glass, and studying the building’s behavior under contemporary conditions. The removed north spire remains a subject of debate and hope; plans to reconstruct it speak to a wider desire to share the basilica’s skyline as once imagined — always with respect for evidence, safety, and context.

Cultural Impact & Media

Saint-Denis appears in scholarship, films, and travel writing as a place where architecture changed direction. It anchors stories about monarchy, revolution, and the persistence of beauty under strain. Students come to learn Gothic’s vocabulary; visitors come to feel how space can shape thought and mood.

From textbooks to documentaries, the basilica serves as a reference point — not only for its historical firsts, but for the way it integrates art, light, and ritual into a coherent whole. Even casual images of its choir communicate a balance of strength and delicacy that has inspired artists and architects for centuries.

Visitor Experience Over Time

Pilgrims, monarchs, scholars, and tourists have crossed this threshold for almost a millennium. The experience has evolved with interpretation, signage, and conservation, yet the essential gestures remain familiar: look up, slow down, let the light lead. The necropolis invites a quieter gaze, the crypt a reflective pause.

As restoration deepened, safety and accessibility improved. Audio guides and tours now help decode the building’s language, making its innovations legible to modern minds. Saint-Denis has become a classroom of stone and color, welcoming generations to learn and to feel.

Saint-Denis during the Revolution & WW2

The Revolution’s desecration in the 1790s marked a traumatic moment: tombs opened, remains displaced, symbols contested. The basilica endured as a wounded witness, later receiving careful efforts to sort, honor, and present the necropolis with dignity and critical clarity.

During World War II, the basilica faced the hardships of occupation and scarcity but survived with limited damage. Postwar decades renewed study and conservation, reasserting the building’s role as a place of culture, worship, and shared heritage.

Saint-Denis in Popular Culture

Though quieter than Paris’s celebrity landmarks, Saint-Denis appears in cultural narratives about the origins of Gothic, the French monarchy, and the northern suburbs’ layered identity. It is sometimes a setting in historical novels and documentaries, a stage for thinking about beginnings and memory.

Its images — rose windows, effigies, choir — travel widely in books and media. For many, the basilica’s fame is intimate: a recommendation from a teacher, a morning of unexpected wonder, a realization that light can feel like thought made visible.

Visiting Today

Today’s visit balances discovery and care. Clear routes guide you through nave, choir, tombs, and crypt; interpretation highlights key moments and meanings. The basilica’s neighborhood adds texture — markets, cafés, and the everyday bustle around a monument that remains a local anchor.

Accessibility has improved where feasible; advance booking reduces waiting; and a range of visit formats let you choose between quiet contemplation and in-depth guided exploration. The basilica rewards time and attention — a place that feels larger the longer you look.

Future Preservation Plans

Conservation plans look to the basilica’s long horizon: stabilizing fabric, studying glass and stone interactions, and, for some, reviving the north spire as a patient, evidence-led project. Debates are thoughtful — weighing history, feasibility, and the values at stake when shaping the skyline anew.

Ongoing research, training, and community partnerships support a living heritage model. The goal is not perfection but stewardship: a resilient basilica that welcomes worshippers and visitors, and a clear record of how we care for what we inherit.

Nearby Paris Landmarks

Explore Saint-Denis’s lively market and square, stroll the Canal Saint-Denis, or pair your visit with the Stade de France. Montmartre and Sacré‑Cœur are a metro ride away, offering a contrast of hilltop views and 19th-century piety.

Head back toward central Paris for the Louvre and Île de la Cité, or discover La Plaine’s contemporary venues. Saint-Denis is a hinge — a chance to connect medieval innovation with modern urban life.

Cultural & National Significance

Saint-Denis is the cradle of Gothic and the resting place of French monarchy — a double heritage that binds architecture and national memory. Its stones articulate a vision where beauty serves understanding and ritual meets the responsibilities of power.

As a living church and monument, the basilica remains a place of encounter: between past and present, local and national, art and devotion. It teaches patience and attention — how to read light, how to listen to stone — and honors the continuity of care across time.